Trust occurs without exception in all business-related activities and scenarios. In fact, it is the foundation of all activities, deals, collaborations, and processes that involve more than one party. In a business context, trust is required with people from inside or outside of the organization. While it is hard to quantify the precise importance of trust, a lack of trust is arguably one of the biggest expenses in business. Trust is a particularly fragile concept, given that it may take years for a manager or an executive to develop the trust of their employees, but can be betrayed within a moment. Trust is the natural result of thousands of tiny actions, words, thoughts, and intentions.

Without trust, transactions would not occur, influence could be destroyed, leaders can lose their teams and salespeople can lose sales.

What is Trust? Trust is a(n) (at least) two-party bilateral social construct that is built when perceived risk and consciousness of vulnerability are outweighed by the perceived benefit that both (or more) parties choose to see before going forward in acting on their intentions. It is a manifold concept made up of thousands of tiny actions, words, thoughts, and intentions. Despite the central role of trust in business today, it can remain unnamed and invisible.

The business strategist David Horsager identified the following eight pillars of trust:

Clarity

People trust the clear and mistrust the ambiguous

Compassion

People put faith in those who care beyond themselves

Character

People notice those who do what is right over what is easy

Competency

People have confidence in those who stay fresh, relevant, and capable

Commitment

People believe in those who stand through adversity

Connection

People want to follow, buy from, and be around friends

Character

People immediately respond to results

Consistency

People love to see the little things done consistently

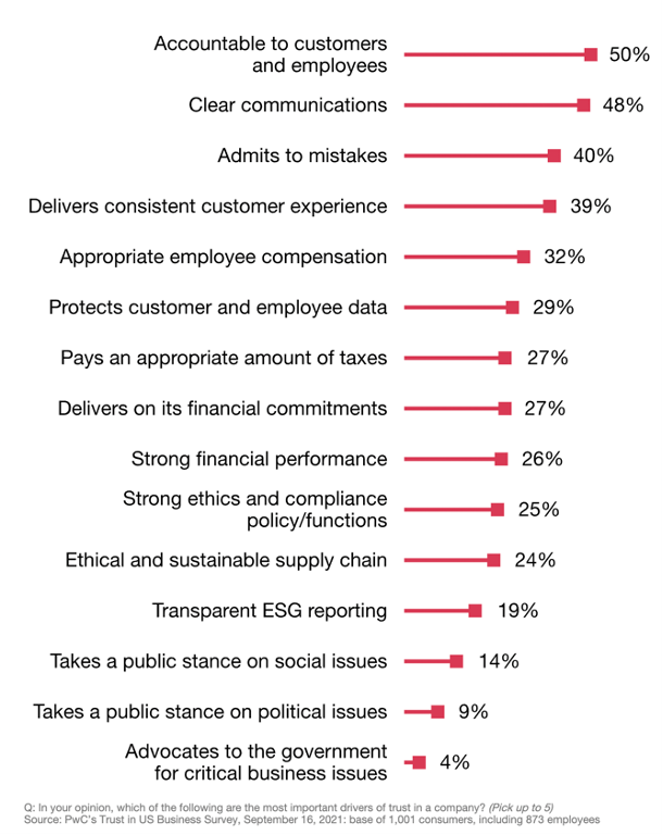

As per “PwC’s Trust in US Business Survey” from 2021, business executives, customers and employers show to think about the same four items when they think about trust: data protection, cybersecurity, treating employees well, ethical business practices and admitting mistakes. Notably, when it comes to points beyond these four elements, the divergences grow. Business leaders tend to take a broader stance on trust including elements of responsibility such as responsible usage of artificial intelligence (AI) and social impact (i.e., sustainable value chain management and ESG reporting). Employees, on the other hand, emphasize more on leadership accountability. This survey merely serves as a benchmark that gives an idea of how much the notion of trust differs depending on socio-economic, demographic, and personal definition. The only statement regarding trust in business that can be made with certainty is that it is a highly complex phenomenon that is yet to be fully understood.

According to the PwC study, established trust in companies pays off in several ways and through various stakeholders: Almost half (49%) of consumers have started or increased purchases from a company because they trust it, and 33% have paid a premium for trust. PwC finds that 44% of customers have stopped buying from a company due to a lack of trust. As for employees, PwC finds that 22% have left a company because of trust issues and 19% have chosen to work at one because they trusted it highly. In other words, one out of five of your employees do not leave for reasons of a higher-paid job or position but because of a lack of trust in the company.

What builds trust in business for consumers and employees

Figure 7: What builds trust in business for consumers & employees

(Source: PwC’s Trust in US Business Survey, 2021)

When it comes to environmental, social and governance (ESG), 45% of business leaders have implemented transparent ESG reporting — but only 19% of consumers list it among the top five drivers of trust. This disconnect between consumers and businesses may be more complex than it first appears. Consumers care deeply about ESG initiatives such as climate change. However, they may not fully understand what ESG reporting entails, or PwC alternatively supposes that customers may consider it as part

of their top two trust drivers (i.e., accountability and clear communications). ESG skepticism may also be a problem. Only 24% of consumers say the main reason for ESG pledges is to do good. Far more (39%) say that the motive for companies lies in self-interest: to build trust with the consumers.

In this next section, a narrower look will be taken at e-commerce trust.

Trust in E-Commerce

With the rise of e-commerce, the concept of consumer trust has been adopted, analyzed, and refined in its meaning and role in the online context. This is to say that different additional layers of complexity have been added to the already diffuse concept of trust in offline business contexts. This particular kind of trust is called online trust and refers to the attitude of the customer which has the confident expectation in an online situation that one’s vulnerabilities will not be exploited. E-tailing websites convey more and more humanistic qualities which mimic its retailing equivalent with actual human interaction to foster trust- building. Though there is no pertinent scholarly definition for consumer trust, the elements of confidence in a product or company, assurance for integrity, and reliability are often named in association.

In e-commerce, the importance of the website’s design and social cues that convey humanlike features as well as the assurance of transaction are builders for trust in businesses. Further, security, privacy protection, and knowledge-based familiarity of the website and its functions have been found to have a positive as well as significant impact on trust.

Overshadowing all that an online vendor can regulate within his/ her sphere of influence is self-efficacy (i.e., initiation, effort, and persistence of the customer). Self-efficacy assesses how well someone can go through a course of action that is needed to deal with a prospective situation, regardless of the actual skill level of a person. It puts other antecedents for trust in the shade in terms of positive influence on transaction trust. Meaning that if a user cannot navigate well through e-commerce, their trust in the e-commerce shop or is impaired as a result even if the skills of the user play a large role in the impairment. With millennials, there is a relatively high perceived risk associated with online purchases as compared to younger generations. Possible incentives that are perceived benefits in the eyes of the customer entail time and cost savings and increased convenience

Concerning benefits, functional benefits rather than affective trust-based ones are found to influence purchase intention the heaviest in multiple studies. Especially the first two named elements can be connected to cryptocurrencies since their transaction time and cost is lower than with alternative payment service providers.

For example, a retailer in the USA selling a product via PayPal costs 2.9% of the sum sent plus $0.30 per transaction within the country. Border crossing trades cost an additional 1.5% of the transaction settling sum. BitPay as a comparable payment service provider in the crypto sector charges only 1% of the sum, regardless of border crossing. This example can be seen as an incentive for the customer and the retailer because, for both sides, the transaction becomes cheaper and thus, more beneficial. The more prevalent the perceived benefit is in the mind of the customer, the more willing he/she is to share their sensitive data. Several studies show that even individuals that are highly concerned with their private data are by a vast majority willing to share their data nonetheless, if they value the product, trust the brand, are offered reward points or other financial incentives. These aspects can often be seen in loyalty point schemes and member rebates. As soon as it is established as initial trust, continuous consumer trust and perceived benefits can be seen as a mental shortcut. Together they serve as a mechanism to reduce transaction- specific uncertainty and influence payment behavior and choice of payment methods. Payment behavior can be broken down from manifold starting points. From country to age, occupation over gender, and financial education-specific segmentation, differences can be pointed out.

Blockchain Technology for Trust Establishment

First of all, it is important to note that blockchain technology is not a trustless technology but rather a confidence machine. The absence of a trusted authority in charge of managing and coordinating interactions over a blockchain-based network does not make it a “trustless technology”. In fact, while trust is less relevant when it comes to the standard operations of a blockchain-based system, it is nonetheless necessary to trust the actors securing and maintaining the underlying blockchain network, to guarantee a sufficient level of confidence in any of the blockchain-based applications operating on top of that network.

Blockchain technology thus produces confidence (and not trust) in blockchain-based systems based on the user’s understanding of procedural and rule-based working, stemming from derived mathematical knowledge and cryptographic rules and mechanisms and long-standing account of its past performance. It increases confidence in the operations of a computational system which is dependent upon its underlying governance structure. To place confidence in the governing party or parties of the computational system, trust in a distributed web of actors is needed.

To place trust in a distributed web of actors the following questions need to be answered:

Is the system governed properly?

Can the various actors involved be expected to act in accordance with the blockchain system’s rules?

The web of actors includes miners and mining-pools, responsible for processing and validating transactions, large commercial operators, such as cryptocurrency exchanges or custodian wallet providers, who can leverage their market power to unilaterally impose their decisions onto their user-base, as well as core developers and social media influencers, whose voice can contribute to shifting the selling point. Regulators and policy makers also have a role to play in the governance of blockchain-based systems, to the extent that they can introduce legal restrictions and constraints to influence the decisions taken by any of these actors.

The governance of most blockchain-based systems has been constructed in such a way as to distribute trust over many actors, with different interests and preferences, so that no single actor has the capacity to unilaterally affect or influence the operations of the overall network. Problems emerge, however, when standard governance practices are threatened in the case of an emergency that calls for decision-making beyond the scope of ordinary procedure (e.g., as in the case of TheDAO attack on the Ethereum network).

Although it is possible to enhance confidence in the proper operations of blockchain-based systems through the introduction of a series of technological guarantees related to on-chain governance, the robustness of the underlying governance system requires a whole different set of constraints that extend beyond the scope of a purely codified protocol and code-driven rules. Hence, in order to ensure a proper level of confidence in such blockchain-based systems, it may be necessary to introduce a series of procedural and substantive constraints related to off-chain governance, addressing both situations of normalcy and states of exception.

If we take another look at David Horsager’s eight pillars of trust, the following theoretical statements for blockchain technology can be derived:

Clarity

People trust the clear and mistrust the ambiguous

Data inserted into a blockchain is clear, transparent, and immutable. It is clear where data is coming from and how and under which parameters it was inserted into the blockchain system and keeps the same record of a ledger no matter which user looks at it.

Compassion

People put faith in those who care beyond themselves

Blockchain as a neutral technology cannot assert compassion unless programmed to do so (i.e., act according to rules and code)

Character

People notice those who do what is right over what is easy

Consensus mechanisms incentivize miners, validators, nodes, developers, and participants in a network to do what is right over what is easy. Doing what is right over what is easy is thus not the easier way but the only way in a blockchain-based system

Competency

People have confidence in those who stay fresh, relevant, and capable

In a sense blockchain technology is an iteration step of digitalization and digitization at the same time. While digitalization is referring to making processes such as sending money digital digitization means moving real-life objects onto a blockchain and making it thus digital, tradable, and divisible. blockchain systems can be seen as more relevant and capable than many other innovative technologies.

Commitment

People believe in those who stand through adversity

Decentralized and censorship-resistant blockchain technology cannot be altered and is committed to a truthful display of reality as fed into the blockchain at a given point in time. Changes made throughout time in a blockchain can be tracked and pinned down.

Connection

People want to follow, buy from, and be around friends

Though blockchain technology is a neutral technology and does not have the ability to build interpersonal connections with its users in the case of cryptocurrencies there is communities building around a network that can act as interpersonal relationships to one to follow by from and be around as well as learn from. Crypto communities often share the same vision and mission for a cryptocurrency project they also often collaborate on projects together giving a feeling of belonging.

Contribution

People immediately respond to results

In the case of cryptocurrencies and permissionless blockchain systems people can immediately participate and contribute to the network and the protocol.

Consistency

People love to see the little things done consistently

As the rules of a blockchain system are set out from the beginning and cannot be altered unless a 50% majority is reached blockchain technology can be considered consistent by nature. depending on the network many blockchain systems are up and running 24/7 which can also be viewed as a means of consistency. Though there are improvement proposals in blockchain systems to change rules as needed blockchain systems generally stay consistent in that they are often times backward compatible with previous versions of the system or alternatively they create spin-offs of an existing blockchain (a so- called fork).

Three Measurable Areas of Trust

In 2018, PwC’s conducted the Global Blockchain Survey which found that 45 percent of companies investing in blockchain technology believe that lack of trust among users will be a significant obstacle in blockchain adoption. Reasons provided for this assessment include uncertainty with regulators and concerns about the ability to bring business networks together. PwC makes suggestions to close this trust gap early by planning cybersecurity and compliance frameworks that regulators and stakeholders will trust from the initiation of blockchain development within a company.

Looking at data from supply chain networks across the retail industry, PwC identifies three key measurable areas often considered the foundation of enterprise trust:

Validity of data

An organization has, to the extent and to the effect, accurately sourced information that holds true when shared with the consumer.

Governance of data

An organization has defined fair business rules to manage data and to align with business processes.

Reliability of data

An organization acts consistently and proactively, in a timely, thought-driven manner.

Generally speaking, enterprises tend to hesitate to embrace emerging technology, especially one that requires a new method in sharing data which blockchain technology would require them to do. Blockchain technology delegates data management back to the consumer and to regulatory bodies. Blockchain Technology cannot only shift trust mechanisms within single business entities but rather in whole industries. For example, in supply chain management. The more companies embrace blockchain, the more networking effects come into place. Supply chain management on-chain can only make sense if all steps along the chain are tracked by all participating parties. As soon as one or more steps and suppliers are not participating, the chain is incomplete and significantly inhibited in its purpose.

With more than a decade of this transformative technology, through the rise of digital commerce, trusting business networks have raised significant questions in transforming IT. As a result, this transformation has redefined technical stacks and has developed new data models. However, technology cannot scale trust within a transaction, hence, to reduce the cost of trust, PwC identified quantifiable metrics in the scope of their study.

Quantifying Trust

Today, blockchain presents an interesting predicament in corporate America with businesses siloed by traditional infrastructures and long-standing processes. With the rise of blockchain technology, businesses are demanding data quality reviews prior to progressing into solutions that apply automated business logic across a value chain. Another issue is presented by the quality of data that is inserted into a blockchain system by an oracle. A so-called oracle is the source of inputs from the real world, oracles thus connect blockchains to external systems.

Although trust is a qualitative attribute, the measure of trust depends on quantifiable metrics. Quantifiable measurements of trust as identified by PwC include:

System behavior

Programs and applications that capture the movement of data, as exhibited by transactions, consensus, or votes.

Content analysis

Using techniques like Natural Language Processing (NLP), deep learning and AI/ML to analyze structured and unstructured data.

IoT & digital identities

IoT devices, QR codes, and web-based identities for cybersecurity.

Social layer

Considering human actors, social aspects, user incentives and motivations, culture, levels of digital literacy, access to technology.

By capturing quantifiable data, enterprises begin to establish governance with a collection of automated business processes, improving regulatory compliance and safeguarding the customer experience. The expansion of blockchain data depends on the migration of enterprise legacy data into building blocks, defining rules for each block that results in enhancements to business outcomes as measured by revenue, customer satisfaction, leaner processes, and automation of manual processes.

Blockchain in the Public Sector

Developing blockchain solutions for the public sector also requires a decision for the blockchain stack. The main issue to solve in the public sector is social trust by the public. To increase trust in the public sector, it needs to be considered which information needs to be captured and stored in the blockchain as well as which information should not be included. In the permanent record to support the goal of trust. This is then followed by consideration of the blockchain protocols, architectures and other technical considerations that deliver the necessary capabilities.

A choice must be made regarding the distributed ledger technology protocols (i.e., Ethereum, Hyperledger, Corda, Quorum), the network options (e.g., public, private, hybrid or consortium), governance mechanisms, security, and cost/duration indications (initial investment and annual operating costs).

In this approach, the initial three-layer design and implementation paradigm is expanded by the social layer (i.e., human actors, social aspects,

user incentives and motivations, culture, levels of digital literacy, and access to technology).

A data layer

The ledger itself is an ”immutable” store of transactional data and/ or records, including considerations of data usability, privacy, and security, authenticity, reliability, integrity, etc.)

A technical layer

The technology stack, including distributed ledger protocols, consensus mechanisms, architectures, peer-to-peer networks, data storage, etc.

Adopting this approach encourages consideration of important design trade-offs among the layers that could help avoid potential misalignments between the technology and its intended area of application, as well as encourage faster adoption and more transformative outcomes for governments.

Trust in Cryptocurrencies

After having looked at trust in the context of blockchain technology, we will now focus on trust in cryptocurrencies specifically. As there is no single entity behind Bitcoin that can help with customer service requests, a user that holds their Bitcoin in self-custody, can in the event of losing their keys for access to their Bitcoins not be recovered in any way. In a sense, instead of trusting payment service providers, trust is replaced upon the payer holding their own cryptocurrency.

There is evidence that trust in an algorithm is more likely when information on others who have adopted it already is available rather than the actual accuracy of an algorithm. Anecdotal evidence and reviews from people that we know, and trust can be a bigger driver of trust than the factual accuracy of an algorithm’s working mechanisms. In the case of blockchain technology, this could mean that anecdotal evidence of people or executives we trust could make us more likely to place trust in the technology. There are different attributes that impact trust in cryptocurrencies. Trust is found to be linked to transferability, immutability, and openness. Cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin, could make international transfers much easier, with lower transaction fees than those charged by traditional commercial banks. Since cryptocurrencies could become an alternative method for international money transfers, several commercial banks worldwide are looking into launching their own cryptocurrencies.

Other trust-fostering factors are ledger immutability and openness - the former securing safe and fair transactions and the latter making the transaction information accessible to the public. Immutability means that the transaction history provided on Bitcoin ledger cannot be manipulated, revised, or deleted.

Openness refers to the availability of the data on the Bitcoin blockchain to everyone, rendering the system completely transparent. Openness creates transparency, while immutability creates accountability. Transparency is considered as the key element in trust creation. The degree of transparency and accountability offered by Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies is unparalleled to that of any traditional financial institution. When technology provides a high enough level of transparency and accountability, it eliminates the necessity of a trusted central authority to govern the system. In other words, it is essentially the core properties of blockchain technology that facilitate the creation of trust in cryptocurrencies.

The geographic locations in which crypto communities are is also where crypto hubs are forming (i.e., through the founding of crypto or blockchain technology-enabled companies, providing point of sales for cryptocurrencies in stores are more frequent, laws and regulations are laxer). These individuals meet the criteria of being at least somewhat knowledgeable and familiar with cryptocurrencies. Exemplarily, Berlin has a district in which almost all stores accept cryptocurrencies as a means of payment, the IT University of Copenhagen offers a Blockchain summer school, in 2018 the Czech Republic counted 147 Bitcoin-accepting stores in 2018 and Malta is also referred to as Bitcoin Island.

It is not possible to assess trust in cryptocurrencies fully as it consists of various layers, angles, and depends on the technical set-up, jurisdiction and what cryptocurrencies are used for.

Who trusts Bitcoin?

Trust in Bitcoin as a means of payment and investment vehicle is more prevalent in segments that fit the profile of male, between 20 and 35, are financially well-educated, and have high levels of self-efficacy in handling crypto payments. The adoption of blockchain technology is measured by how well it is understood and trusted.

Lack of knowledge is found to significantly limit trust and usage intention. Another trust influencing factor is the reinvolvement of a third-party payment service provider. It does not necessarily mean that by introducing a payment service provider, Bitcoin’s features lose their trait of being perceived as a trustless system. It can be even beneficial for building trust to have a tangible contact company. In terms of functional benefits, retailers can mitigate volatility risk and shift the financial risk connected to Bitcoin. To sum up, it depends heavily on the convictions of individuals whether increased trust in cryptocurrencies is achieved by reintroducing a third party or by removing the third party.

Established trust in existing payment methods does not significantly influence usage frequency (for example ApplePay, PayPal, etc.). Trust also does not appear to be an irrefutable prerequisite for usage, especially not for payment methods that customers are completely unfamiliar with and thus, hold a higher perceived risk of uncertainty. Bitcoin does fulfill the requirements of acting as a payment method in that it has comparable features such as trustworthiness, transaction speed, cost, crossing international borders, etc. to other existing payment methods. Even though initial trust in Bitcoin as a payment method is not established with most people, it does not mean that Bitcoin as a payment method would only be used by those that trust it. Trust in Bitcoin in general and trust in Bitcoin as a payment method are two different things where trust in one does not necessarily imply that trust in the other is established as well, though there is a tendency that those who do trust Bitcoin also trust it as a payment method.