The international regulatory landscape is fragmented, with national legislations ranging from no regulation to explicit prohibitions, to comprehensive integration into the financial industry. In the following, you will learn about blockchain and crypto asset regulation in general and look at specific jurisdictional differences.

Risks connected to crypto regulation

The growth of the crypto market continues to be high despite the traditionally extreme price fluctuations, there is currently no flattening of this trend that can be observed at present. New, innovative developments are constantly observable in the market. Crypto assets are gaining importance for more and more jurisdictions. During this, regulators all around the world are trying to keep up with the developments, by gathering relevant information and gradually acquiring the necessary knowledge. In doing so, they encounter two inherent characteristics of crypto assets that continue to prove challenging:

The decentralized structure makes it difficult to identify a competent authority to take responsibility for any questions or responsibility for any questions or problems that arise.

Pseudonymity, i.e., the limited traceability of transactions and identities of sender and recipient, exacerbates this challenge in the case of further in the case of illegal activities.

The use of crypto assets is possible in many countries without or with few restrictions. In the case of particularly decentralized, globally operating blockchains, even restrictions on the part of state supervisory authorities are almost impossible to enforce. This results in risks, with which various challenges. These are analyzed in more detail below.

A significant risk, which traditionally has a cross-border character and requires a high degree of international cooperation, is compliance requirements in connection with:

Anti-Money Laundering (AML)

Countering the Financing of Terrorism (CFT)

Identity verification

(Know Your Customer, KYC).

The decentralized structure of cryptocurrencies enables users, transactions in the form of direct money transfers without the need for any regulated intermediaries, thereby bypassing (otherwise established) controls to be circumvented. For the exchange of crypto assets into official currencies, intermediaries such as crypto trading platforms, for example, are required. The peer-to-peer nature of crypto assets makes it difficult for the competent authorities to fulfill their regulatory obligations and to and to track suspicious activity.

Even though crypto assets are already regulated in some countries, the laws in force usually differ greatly. This heterogeneous regulatory landscape complicates international cooperation on money laundering, terrorist financing, and in enforcing sanctions or embargoes. It is also more difficult to detect the origin of funds to avoid tax payments.

Already today, there are global guidelines for the handling of crypto assets in the context of AML and CTF. These are driven in particular by the recommendations of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), which is a state-independent body that sets international standards to prevent potentially illicit activities. Since the extension of global anti-money laundering and counterterrorist financing standards to crypto service providers in 2019, the FATF produces an annual report that tracks the progress of participating countries tracked in implementing the recommendations.

In 2021, 27 of the 38 FATF members have already implemented or are working to implement required AML/CFT legislation for crypto service providers.

But this initially high increase should be viewed in relation to the total cryptocurrency transaction volume, which grew by a full 567% compared to 2020. Overall, money laundering in 2021 accounted for just 0.05% of total crypto transaction volume-the lowest level in the past five years.

The fact that such statistics exist at all shows that, on the one hand, transactions on the blockchain are indeed well-tracked due to its transparency by companies such as Chainalysis. On the other hand, does not mean that it is easy to identify the parties involved. This is because pseudonymity means that flows of money cannot always be unambiguously assigned, in case of illegal activities, the responsible persons or organizations can be held accountable. But progress is being made here as well: Companies such as Chainalysis19 are specializing in transaction monitoring to detect and prevent illegal activity. Here, there is more talk about Know Your Transaction (KYT) and less about KYC, as transaction histories are continuously monitored in real-time to identify and detect patterns of illicit intent.

Operational risks

Another aspect that is relevant from a risk perspective is the operational risk in dealing with crypto assets and the associated use of blockchain infrastructures. In traditional payment transactions, in the event of an error, this can be reported to the central administrative body (e.g., in the case of an IBAN transfer, to one's own bank) and, depending on the rules, the transaction can be reversed or cancelled. This type of reversibility is generally not possible with blockchain-based transactions, since transactions are possible, as transactions are final and there is no centralized management point where errors can be reported and resolved. Thus, consumers generally have no claim to the reversibility of a transaction. In the event of errors, corresponding funds are thus lost unless no regulated intermediary in the form of a crypto service provider is used. In addition, consumers and investors using cryptocurrencies can lose portions or all their assets if they lose their private key or if it is stolen.

This risk exists with both custodial and non-custodial wallets. In the case of custodial wallets, the responsibility for the secure storage of the private keys is the responsibility of the third-party provider. Such a company can then be attacked, for example, by hackers using an insufficiently secure IT environment. Through such illegal access, investors may lose all or part of their crypto lose all or part of their crypto assets. The past few years have shown that such security vulnerabilities occur in the crypto market and the market and that the risk of hacking attacks continues to be present.

If the custodial wallet provider loses the private key of its customers, they can potentially claim compensation. This security does not exist with non-custodial wallets. Here, the responsibility for protecting the private key lies with the investor himself. The use of non-custodial wallets, therefore, entails greater responsibility for consumers and investors. For consumers and investors: If they lose their private key, all funds on the wallet are also irretrievably lost.

Consumer risks

Consumer and investor protection are two of the most important legislative priorities. With the emergence of innovative and lightly regulated business models, there is an increased risk for consumers to fall victim to unfair and fraudulent activities. This can also be observed in the crypto market. Consumers and investors are losing their assets time and again due to fraudulent schemes, market manipulation, hacker attacks, or lack of deposit insurance with crypto service providers. Two factors are highly relevant here: The first is a lack of knowledge about the crypto market on the part of consumers and non-professional investors. Many of them are not aware that they are trading in an environment that is not yet regulated. Mistakenly, the crypto market is compared to traditional financial services. In many cases, this leads to incorrect risk assessments.

Second, indirect risks arise for consumers and investors when dealing with regulated crypto service providers. It is true that the responsibility and risk for losses lie with the crypto service providers. Nevertheless, insufficient capital requirements for crypto service providers in the event of insolvency or similar financial crises for investors can lead to a partial or total loss of their assets (liquidity risk). In this context, the lack of deposit insurance may also be in the form of the separation of assets under management and assets under custody can also lead to similar consequences (credit and default risk).

In addition, the protection of customer data is relevant. In many jurisdictions, there are already existing data protection regulations. Due to the transparent nature of blockchains, the question then arises to what extent existing regulations should be considered in blockchain-based and pseudonymized data transparency. In particular, the lack of accountability and accountability of cryptocurrencies can pose a challenge.

In the following section, you will learn how nearly any right and therefore any asset be tokenized based on the Token Container Model from Liechtenstein.

Liechtenstein’s token Act

In January 2020, new blockchain laws came into force in Liechtenstein. Based on these laws, companies and entrepreneurs can tokenize any right and therefore also any asset in a straightforward way.

Then, complex workarounds or far-fetched interpretations of decade-old paragraphs are not needed anymore. This will provide legal certainty and inevitably lead to the emergence of the token economy. Standardized processes and registered service providers for tokenization will be emerging in Liechtenstein. This will significantly reduce the time and cost needed for tokenization processes. What exactly will be tokenized? Almost everything.

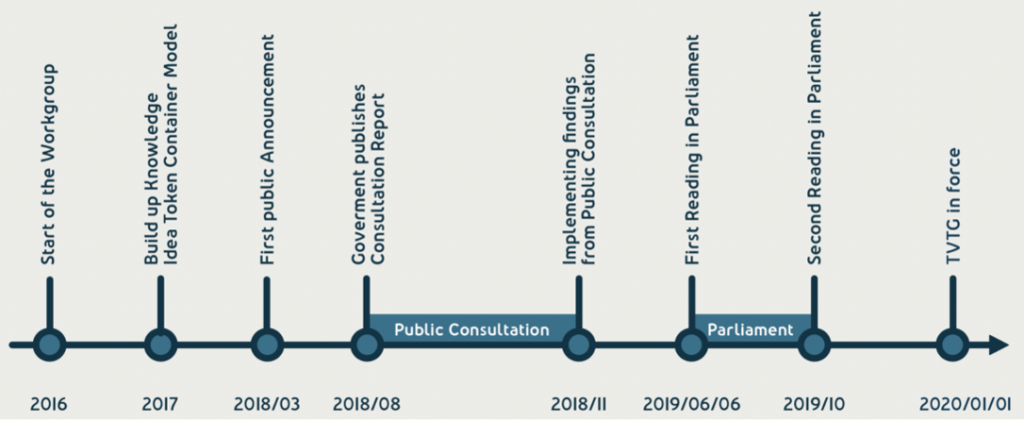

Figure 11: Milestones of the Liechtenstein Blockchain Act coming into force on January 1, 2020 (Source: NÄGELE Attorneys at Law LLC, 2019)

Precisely, the Liechtenstein Blockchain Act is actually called “Tokens and TT Service Providers Law” (TVTG) but we will, for the remainder of this article, use the former expression. Also, the new law uses the generic word “trustworthy technology” (TT) which can include blockchain and DLT systems.

The Liechtenstein Blockchain Act is a collection of new rules and changes of existing laws that allow rights and assets to become tokenized. Tokenization means that as of January 2020 nearly any right or asset can be “packaged” into a token according to the Token Container Model.

Liechtenstein thereby acknowledges that — driven by digital transformation — the physical world as we know it for hundreds of years will sooner or later be augmented by a digital world. Often, we use paper documents to agree on a contract or for proofing evidence. This contracts then “creates” rights for the involved parties. Notaries are responsible to print, read and verify identities and documents — mostly all processes are conducted on paper.

The Liechtenstein Blockchain Act now acknowledges that such paper-based rights and assets (yes, they can also be written on a PDF-document and signed digitally) can and will be brought to the digital world and will become tradeable easily: in the form of tokens. If thousands of rights and assets will be represented by digital tokens in a couple of years, we suddenly have two worlds: (1) the physical world as we know it and (2) the new digital world, which includes a subset of the rights and assets of the physical world. To become practical: But who is actually owning my house? The person in the real estate register? Or the person owning the token? What if the token is being stolen, or lost?

The Liechtenstein Blockchain Act also integrates the fact that the physical world always needs to be in perfect synchrony with the digital world of the tokens. This is very important because tokens can be, for example, lost or stolen. Also for this reason, Liechtenstein amended the civil law which is truly fascinating. This, by the way, is one fact that makes the Liechtenstein Blockchain Act really outstanding and, in our mind, a best-in-class framework.

The Token Container Model

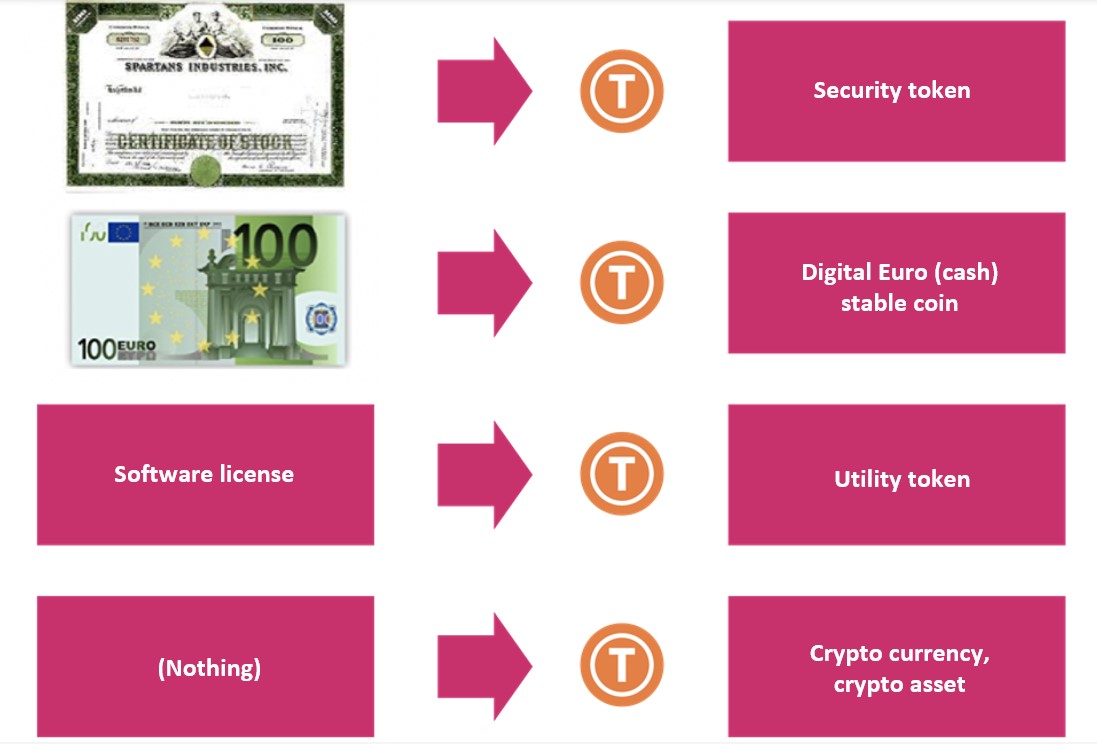

One of the building blocks of the Liechtenstein Blockchain Act is the so-called Token Container Model (TCM). With this framework, a token serves as a container with the ability to hold rights of all kinds. The container can be “loaded” with a right that represents a real asset such as real estate, stocks, bonds, gold, access rights, money. But the container can also be empty. The latter case applies for example to digital code — the most notable example being Bitcoin.

This approach of loading a right or asset into a container (i.e., into a token) may sound trivial but allows a separation of (1) the right and the asset on the one hand side and (2) the token technically “running” on a blockchain-based system on the other hand side. In this manner, Liechtenstein differentiates between (1) law and (2) technology.

Therefore, this model is truly helpful to understand the process and the impact of tokenization. All rules governing the right and the asset basically stay as they are. But some specific rights are changed through the digital nature of the right packaged into a token. Here is an example: Some people think that security tokens (i.e., a stock on a blockchain system) are a new class of securities. But the Token Container Model makes it very clear that a security token is nothing else than a security (with all the rules, licenses, duties etc. applying to it) technically “packaged” into the token which loads the security like a container. The word “container” is meant literally. The token can now be transferred to new owners, can be managed in a portfolio, or can safely be stored by a custody provider — without the right and asset within the container changing. To illustrate this for clarity:

A right is virtually stored in a container representing the token and running on a blockchain-based system. The right could, for example, be the ownership right of a diamond. Whoever owns the token owns the diamond — exactly this relation is established by

the Token Container Model. The diamond does not need to move its physical location; it can remain in a vault. But the ownership of the diamond can change by transferring the token to other persons. This would make sense for a private person storing value by owning a diamond but also for institutional investors who build entire portfolios of fractionally owned diamonds (think of 1.000 investments in fractions of a diamond for the purpose of risk diversification).

The Liechtenstein Blockchain Act

Liechtenstein did it! In the beginning of October 2019, the second hearing of the Liechtenstein Parliament on the new Liechtenstein Blockchain Act took place. No significant issues arose during this hearing. The result is that the Liechtenstein Blockchain Act will come into force in January 2020 and allows straightforward tokenization of all kinds of assets and rights without legal workarounds.

1

takes the physical asset in custody

2

Token represents the right

3

disposal over the Token results in the disposal over the right!

Figure 12: Token Container Model representing a right on a diamond in a container such that it can be transferred easily without moving the physical asset in custody

(Source: NÄGELE Attorneys at Law LLC, 2019)

This model is progressive and provides legal certainty for pre-existing rights that are tokenized as well as for the information stored on blockchain-based systems. Note that Liechtenstein amended its civil law to allow the token world to have priority over the physical world for the cases where tokens exist for rights and assets.

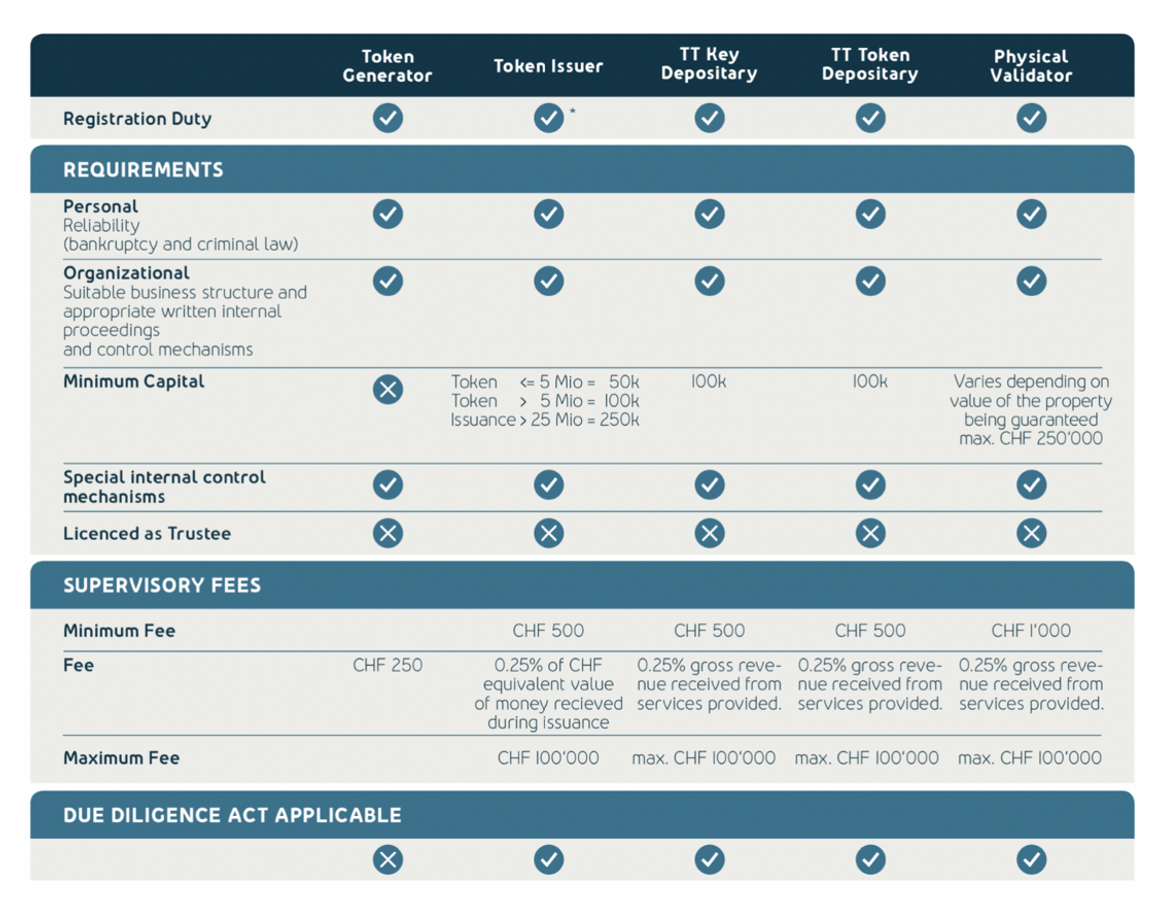

The physical validator has the duty to integrate the physical with the digital world

One guiding principle of the Liechtenstein Blockchain Act is that some new service providers that interact with the blockchain and the tokens need to be regulated. Some of these new formats of service providers need not only a registration with the Liechtenstein Financial Market Authority (FMA), but also a license to operate. One of these new roles is the so-called physical validator. Their role is to integrate the physical world into the digital world.

The physical validator has the duty to identify the holder of the tokens. In the previous example with the tokenized diamond, the physical validator knows who is owning the token and, with it, the diamond and has the duty to ensure the contractual enforcement of the represented rights and obligations, e.g., by storing the assets (or rights) of the real world in a vault.

This is done by the physical validator. He also has the responsibility for having established correct business processes. If errors occur, if the physical assets are stolen or damaged, or if he does not comply with the rules, it is his responsibility to solve these issues. If he is not capable to do so, he risks his license as a service provider and therefore loses the right to operate. With this approach, the Liechtenstein Blockchain Act assigns the responsibility to guarantee perfect synchrony of the physical world and the digital world to the physical validator. Therefore, the newly defined role of the physical validator is highly important as it enables the token economy: providing certainty and allowing the tokenization of an existing right and its subsequent valid transfer onto a blockchain system.

Tokenization of any right and asset

According to the Token Container Model, any asset or right can basically be represented by a token. Some examples can be seen below. For example, a software license right or an access right can be put into the token container. In most jurisdictions, this would be classified as a utility token. If the token is sold to the market before the development of the product has actually been finished, this process is called Initial Coin Offering (ICO). Next, applying the European E-Money framework would allow to package traditional currencies such as the Euro or the Swiss Franc into a token. These tokens would be classified as payment tokens, more precisely, Euro tokens, digital Euro, Euro on blockchain, cash on ledger, etc. This is nothing else than putting a Euro into a token by applying E-Money rules for the content of the container. Ultimately, a security can be packaged into the token. Then, all securities’ laws apply, and the result is a security token. If sold to investors, we call this process a Security Token Offering (STO).

Figure 13: Examples for the Token Container Model (based on Dünser, 2018)

Tokenization follows a life cycle

When a right or an asset is tokenized, first, the tokens need to be generated technically. Then, the tokens need to be issued to the new holders. This can take place in a token sale (e.g., STO, IEO, ICO). Tokens then can be traded against other tokens and in most cases, they need to be custodied. Even more so, tokens — in the financial market — can be purchased and placed in a portfolio for investing purposes etc. To put it in a nutshell, tokens have a life cycle. Different events in the life cycle of the token indicate different requirements of the actors, e.g., token generator, token issuer, token depositary. The Liechtenstein Blockchain Act therefore provides multiple possibilities to register with the FMA such that companies can act along the life cycle of tokens. As Figure 4 points out, companies can soon apply for these registrations. There are multiple requirements for the applicant. And, of course, licenses are not for free. But comparing the fees and requirements for other registrations or licenses of financial authorities indicate that fees for licenses in Liechtenstein are reasonable. Once clearly defined registrations exist, as is the case in Liechtenstein, and once tokenization processes and smart contracts become standardized, ultimately costs for tokenization of any asset will be brought down.

Figure 14: Overview of 5 of the 10 registration requirements

(source: NÄGELE Attorneys at Law LLC, 2019)

Liechtenstein and other countries

Liechtenstein sets forth a technologically neutral and all-encompassing framework designed to capture all aspects of tokenization. Due to Liechtenstein’s status as a member of the European Economic Association (EEA), compliance with codified EU/EEA guidelines and regulations is required. These base line regulations create a floor that Liechtenstein legislators can build upon. The registrations and licenses issued under the foundational regulations and directives of the EU/EEA are passportable to other EU/EEA member states, while the Liechtenstein unique registrations under the Blockchain Act are not passportable. Of course, tax regulations in other countries and the upcoming “crypto license” in Germany might make business endeavors here and there more complex but not unfeasible.

At the core, the Liechtenstein Blockchain Act is focused on adapting pre-existing laws to foster legal certainty within the token economy. Drawing a clear line between what falls under civil law versus regulatory and supervisory law, the Liechtenstein Blockchain Act includes changes of the Liechtenstein Persons and Companies Act, Trade Act, Due Diligence Act, and Financial Market Authority Act. Probably the most important aspect are the changes in the civil right, to ensure that the underlying right represented by the token is effectively transferred from party A to party B. Besides this, the act provides regulatory and supervisory rules regarding those interacting with blockchain systems — including consumers, service providers, and intermediaries.

Liechtenstein: “straightforward tokenization” without workarounds

In case you try to tokenize rights and assets, this is typically difficult and challenging with local laws in place. In Germany for example, specific forms of debt can be tokenized but no shares or bonds up to now. A skilled lawyer is always necessary to try to find a workaround and — subsequently — convincing the regulatory bodies that the proposed workaround is complying with the local law by interpreting some paragraph of the law in a “new” way. The lawyer of course would never call this workaround a workaround. Nevertheless, it is often possible but not easy. Typically, such workarounds are also expensive since they are not yet subject to a standardized process. Therefore, Liechtenstein is an attractive destination for various tokenization efforts: Without time-consuming and costly efforts, rights and assets can be tokenized in a straightforward way. No workarounds are required as in other countries. This did not only standardized processes but also decreased the costs for tokenization processes significantly. However, since its introduction, the amount of goods tokenized with the TVTG was well below the expected numbers.

To dive into the regulation of asset tokenization specifically and the process of tokenizing, watch this Generation Blockchain video.

The current EU market around crypto assets is characterized by continued strong growth of a wide variety of use cases. Driven by the interest of private individuals, investors and companies from many industries, the industry continues to attract high demand despite extreme price fluctuations.

Definition of a cryptocurrency under the German Banking Act (KWG)

For a long time, there was no uniform definition of the term cryptocurrency. The term was used synonymously for different aspects of the blockchain ecosystem. Through the European Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation (MiCAR) as well as the German Banking Act (KWG), two definitions have now been established in the European area. In doing so, both definitions introduce the new term crypto value instead of cryptocurrency. The preliminary MiCAR definition for crypto assets is thereby broad and includes various subcategories. The KWG shows parallels to MiCAR, for example in digital mapping and transferability, but takes a different approach: In its definition, the KWG specifies the decentralization and corresponding governance of digital assets and thus clearly distinguishes crypto assets from existing monetary assets.

Thus, the definition according to section 1 para. 11 sentence 4 of the KWG: "For the purposes of this Act, crypto assets are digital representations of a value which has not been or guaranteed by any central bank or public authority and does not have the legal status of a currency or of money, but which may be used by natural or legal persons or legal persons on the basis of an agreement or actual means of exchange or payment, or for investment purposes, and which can be transmitted, stored, and traded electronically, stored, and traded by electronic means. " Crypto assets are thus a category of decentralized assets, such as Bitcoin and Ethereum. Building on the KWG definition, crypto assets are thus defined as follows:

A crypto-value is a digital asset that is created using a distributed ledger technology (DLT) and cryptographically secured.

Crypto assets have no existing central authority, for example in the form of a government agency or legal person/entity.

Crypto assets have no intrinsic value and no hedging by assets with intrinsic value.

Markets in Crypto Assets (MiCAR)

To understand crypto assets, it is important to establish some definitions and content boundaries. For this purpose, we use the existing legal texts from the European area as a basis. The law is set to create parameters for how each of the European Union's member nations regulates crypto. It is expected to create a common licensing regime, enabling companies operating in one member nation to launch in the others, as well as define rules for issues such as stablecoin issuance. The MiCAR’s definition of crypto assets is not compatible with the term used in the German Banking Act (KWG), thus changes are also expected to the German market.

The MiCAR contains the following three sections:

The authorization procedure for issuers of crypto-assets and the corresponding obligations for the token types covered by the regulation (asset-referenced tokens, e-money tokens and, as a catch-all provision, crypto-assets).

The authorization procedure for crypto asset service providers.

The competent authorities and their competencies.

MiCAR has been created to introduce regulations on the licensing and supervision of crypto asset providers and their issuers. The focus is on issuers of asset-referenced tokens and e-money tokens. Thus, only legal entities that are established in the EU and have received a corresponding authorization from the competent authority may provide these services from 2024 onwards. An important component of the MiCAR is therefore the licensing regime established under it by the respective competent authorities.

Under the final deal, any crypto service provider with over 15 million active users would be subject to supervision at the European level tarting in 2022 when it comes into force. After an 18-month transition period, MiCAR will then become directly applicable in all member states. Thus, a harmonized set of rules for crypto assets in the European Union can be expected in 2024.

The text stems from the academic article “Liechtenstein Blockchain Act: How can nearly any right and therefore any asset be tokenized based on the Token Container Model” published on October 7th, 2019 by Prof. Dr. Philipp Sandner, Dr. Jonas Gross and Thomas Nägele. The authors consented to the use of the text for the purpose of the Generation Blockchain project.

The currently fragmented regulatory landscape is an impediment to international regulation. To create efficient and holistic regulations for the handling of crypto assets there is a need for cross-border initiatives. But to date, individual jurisdictions have taken their own approaches to regulating crypto assets, which consequently differ also differ in their level of development. To analyze the progress of different legislations across jurisdictions, a standardized framework was published based on the analyzed risks. It shows a holistic status of the regulation of a respective jurisdiction and thus enables comparisons and assessments. The framework serves as a tool to identify the regulatory risks relevant in the regulatory issues in the context of cryptocurrencies.

Before evaluating a particular jurisdiction against the framework, it is necessary to determine the extent to which the jurisdiction in question has an explicit or implicit prohibition on crypto assets. An implicit prohibition in this context would be, for example, that companies are prohibited from offering crypto services. In these cases, the application of the framework is not purposeful. The framework consists of two overarching categories, divided into twelve evaluation criteria. These can be evaluated using a rating scale.

In the first category, the financial regulatory treatment of cryptocurrencies in each jurisdiction is assessed based on the following factors:

Crypto values regulated as financial instruments

Classification of crypto assets as financial instruments recognized by regulators.

Fiscal regulation in place

Existing tax regulations for dealing with crypto values for both individuals and businesses.

Regulation of wallet infrastructures in place

Existing regulations on custodial and non-custodial wallets in the context of private keys and custody of crypto assets.

Regulatory responsibility settled

Clear mandating and delineation of responsibilities of authorities regarding supervisory duties in the dealing with crypto assets.

Since crypto service providers play an important role in the crypto ecosystem, the second category sets out the regulatory requirements for crypto service providers under governance and consumer and investor protection are assessed based on the following factors:

Capital requirements regulated

Obligations to hold of equity to mitigate credit and default risks.

Risk disclosure and profile for retail investors regulated

Obligations to inform customers about risks in dealing with crypto assets as well as categorization of customers according to risk classes.

Deposit security regulated

Regulations for the protection of customer deposits, e.g., by separating the assets of customers from the assets held for their own assets.

Protection of customer-relevant data regulated

Data protection regulations for crypto assets or possibility of applying existing regulations to crypto assets.

The third category regards governance of crypto assets and blockchain systems:

AML/CTF Compliance Regulated

Requirement to compliance with national and/or international regulations to combat money laundering and Terrorist Financing.

KYC Requirements regulated

Regulations governing the identification and verification of (prospective) customers on the basis of personal data.

Licenses in place

Existing licenses for the provision of crypto services or approvals as a provider of crypto services.

Requirements for IT security regulated

Requirements for the protection of IT systems incl. corresponding security precautions.

The individual factors are evaluated using a scale that represents the degree of fulfillment of the respective factor. It should be noted that the assessment is not dichotomous, consisting of "fulfilled" or "not fulfilled", but rather can take on different characteristics. The degree of fulfillment can therefore also be understood as a process. New developments in the market can thus result in modifications to the regulatory factors. In addition, the degree of fulfillment should not be understood normatively: A high degree of compliance is not per se "positive," and a low degree is not per se "negative”.

Rather, the goal of the framework is to provide an objective assessment that can separate the characteristics of an individual jurisdiction in accordance with its qualitative characteristics. In particular, depending on the perspective from which it is viewed, characteristics can be interpreted positively and negatively depending on the angle. For example, from the perspective of the investor, a regulation of crypto securities is to be evaluated positively.

From an innovation perspective, on the other hand, regulation can be evaluated negatively, because it makes new business ideas in the crypto sector more difficult, prevents them or favors established companies. The valuation model must therefore always be viewed in the context of the individual consideration of the topic of crypto assets.

In order to create an appropriate regulation of crypto assets, the interests and ideas of all market participants and stakeholders should be understood and brought in. In case of conflicts of interest (e.g., between investor protection and innovation), a balance must be found. In doing so, the interests in the crypto market sometimes diverge strongly. It is a balancing act: on the one hand, legislators must ensure that consumers and investors are sufficiently protected from illegal activities as well as inherent risks. On the other hand, such an emerging market should be given the freedom to develop.

The following suggestions can serve as guard rails in this regard serve. First, there needs to be a concrete delineation between the user groups to ensure regulatory treatment that is appropriate for the target audience. Similarly relevant is the clear examination of the areas of application of crypto assets that are currently being used and will be used in the future. This is because the degree of risk of the user groups and areas varies greatly. Corresponding risks can then be better addressed on the part of the legislator if as many manifestations of risks as possible are considered.

The Travel Rule

The FATF's Travel Rule provides, among other things, that crypto service providers above a limit of 1000 euros are required to report information on senders and recipients of transactions to a government institution (Cf. Financial Action Task Force (FATF), 2021). The FATF's Travel Rule allows legislators to implement an approach that is risk-based and appropriate to the target group (in this case (here: investors). At the same time, this Travel Rule also leads to considerable requirements and efforts on the part of crypto service providers. These consequences should be discussed and weighed against each other. An elementary component and fundamental area of application of crypto assets is their safekeeping. It represents the starting point for other applications and increases security for users when dealing with crypto assets. In Germany, legal certainty was already ensured in 2020 through the crypto custody license, anchored in the KWG.

A collaborative approach to regulation

Furthermore, for a professionalized market, especially from the perspective of consumers and investors, trustworthy market participants and service providers are required. To this end, the institutionalization and supervisory control of crypto service providers is particularly useful, as these are usually the first points of contact between users and crypto with crypto assets. At the EU level, crypto service providers and their different roles are being acknowledged in the context of MiCAR are appreciated and comprehensively regulated. In the dynamic and complex crypto market, therefore, there is a need for ongoing collaboration between providers and legislators is strongly recommended. Legislators should permanently seek insights from the crypto industry, to gain a good penetration and up-to-date understanding of the market. As part of this process, regulatory approaches should always be questioned based on new developments and modified if necessary. Finally, due to the cross-border nature of cryptocurrencies, international cooperation is needed involving global bodies such as the FATF, the Bank for Bank for International Settlements (BIS) or the Financial Stability Board (FSB), as well as national organizations such as central banks and supervisory authorities. In addition to standardization of processes and optimized coordination between different jurisdictions, regulatory arbitrage can be kept low. Studies to date have shown that increasing regulation can reduce the overall market activity of crypto assets does not weaken. There is no significant migration of business activity from supposedly more regulated jurisdictions to less regulated jurisdictions observed.

Doesn’t decentralized equal unregulatable?

Various legal standards and rules of order create reliability and legal certainty in the analogous financial economy. An application of regulation in one world and a lack of access in the other world leads to a distortion of competition. The German financial supervisory authority has therefore already taken a clear stance on the principle of "same business, same rules” positioning. In the blockchain community, there are doubts that regulatory institutions will be able to enforce this mandate in the digital business world. This neglects several facts at once.

First, transactions of large amounts cannot be hidden. Second, the traces of Internet activities are much easier to find than the famous black money suitcase. Third, it is sufficient to prove actors and activity to take supervisory action. Decryption is not mandatory for the commencement of prosecution is not mandatory. Fourth, most market participants are interested in creating value within the legal order.

The institutions of banking and financial supervision are currently observing the scene closely and have set up corresponding divisions/departments, in which the necessary know-how for regulatory intervention is being gathered. In the ICO market, one can already see how regulatory interventions are being implemented and enforced. Many countries with different economies (e.g., Australia, China, Dubai, UK, Canada, South Korea, Russia), including previously ICO-friendly havens such as Gibraltar, are currently taking measures to put IPOs and ICOs on an equal footing or create a regulatory framework for blockchain applications. In the digital currency space, the responses from monetary regulators are also broad. There is no central bank that does not permanently track the artificial currency market. In authoritarian economies with high levels of state intervention, national coin currencies have already been announced. This reflects the attempt to bring the market for artificial money under control. In more liberal economies, people are following the cryptocurrency development with attention and are betting that cryptocurrencies will fail due to the difficulties of monetary control.

Most independent central banks assume that the task of regulating cryptocurrency of regulation will therefore fall to them evolutionarily for the digital world as well. The real question is therefore not so much whether it is possible to carry out unregulated digital transactions, but whether it is possible to make the transactions legally secure and court-proof. The design of smart contracts and smart finance in terms of their compatibility with the private and public legal systems will be decisive for the mass suitability and thus the economic commercial success of blockchain applications. The regulatory authorities in the European Union so far see no reason to intervene in what is happening because the activities are too insignificant and because governmental interventions do not occur arbitrarily. The actions of regulators in other economic systems, however, give an impression of the possible options for action and potential consequences.